So, no big surprise, I'm lazy. I realize at some point I'll quit checking Winlink regularly. Of course, that is exactly the time someone will send me something interesting.

So how to make my Winlink messages visible with no effort. Of course, put them in the email inbox.

I already have pat running on my LAN so checking Winlink is a simple matter of pointing my browser. My email client checks for email from my provider every so often, so the first step is to have pat check for inbound Winlink messages every so often. This is no big deal, simply put a pat connect command on the cron tab and away we go.

I decided to check via telnet since from time to time I will swipe my Winlink radio for some other service. I do intend to fix that in the near future so I can be assured the RF path is available.

I decided to log the results. Since the dialog from the RMS is usually pretty boring, I only keep the most recent. Errors, tho, I want to see whether something happened when I wasn't looking. So I wrote a little script:

So, now any Winlink messages are sitting on the Raspberry Pi, how to get them to the inbox.

pat puts everything of interest in the ~/.wl2k directory tree. Received messages are put in the ~/.wl2k/mailbox/(call)/in folder. The messages are stored in plain text, so it would be a simple matter to mail them. Rather than try to keep track of wich messages have been mailed, I decided to move the processed messages into Winlink's archive folder.

The Linux mail command makes this pretty straightforward. Note that your ISP or email provider may have some hoops to jump through in order to make this work. In my case, it was pretty easy. The only slightly tricky part was fishing the subject line from the original messages so when they got to my email client I knew what I was looking at.

The Raspbian implementation of bash seemed to be a little different than those with which I am familiar, and I am not that much of a bash maestro anyway, so I decided to script it in php. This does mean you need to install php, but that is pretty easy.

The following is my script:

<?php

/* Send incoming Winlink to email, then move to archive

*

* jjmcd - 190628

*/

/* Location of Winlink mailbox */

$mailbox="/home/winlink/.wl2k/mailbox/WB8RCR";

/* Address messages will be coming from */

$from_address="wb8rcr@chartermi.net";

/* Address to send messages to */

$to_address="wb8rcr@arrl.net";

/* Subject prefix to ease processing on receiving end */

$mail_prefix="PAT01:: ";

$list = dir($mailbox . "/in");

/* Loop through files in inbox */

while ( false !== ($file = $list->read()))

{

if ( substr($file,0,1)!="." ) /* Ignore this directory */

{

$got=0;

/* Read the file until we find the subject line */

$f = fopen($mailbox . "/in/" . $file,"r");

while ( $line=fgets($f,1000) )

if ( !feof($f) )

{

if ( substr($line,0,7)=="Subject" )

if ( !$got )

{

/* Strip off the "Subject:" part */

$subj=substr($line,9,strlen($line)-11);

/* And remember we found it */

$got=1;

}

}

fclose($f);

if ( $got )

{

/* Build the mail command */

$command = "mail -s \"" . $mail_prefix . $subj .

"\" " . "-r \"" . $from_address . "\" " .

" \"" . $to_address . "\" <" . $mailbox .

"/in/" . $file;

exec($command);

/* Move the processed file to archive */

$mvcommand = "mv " . $mailbox . "/in/" . $file . " "

. $mailbox . "/archive/";

exec($mvcommand);

}

}

}

$list->close();

?>

If you are lucky, the only things you might want to change are the first few lines. After that, the script does a directory listing of the inbox (ignoring the . and .. files). It then loops through that list, opening each file and finding the Subject: line. It pulls the string Subject: off that line and adds $mail_prefix (the mailer will add Subject: back).

The mail command is formed and sent to the shell, then the mv command is also sent to the shell. The script then goes on to the next file.

This script is then scheduled on the crontab shortly after the mail was retrieved from the RMS. I suppose it might have been better to do both in one script, but it can be easier to take a step at a time.

Showing posts with label Raspberry Pi. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Raspberry Pi. Show all posts

Saturday, June 29, 2019

Wednesday, June 19, 2019

Winlink On Your Browser

For those not familiar with Winlink, it is basically radio email. You compose a message in an email-like client. You then connect to a mail server and off your message goes. The interesting thing is that you can connect to the mail server by Internet, but also by radio. There are hundreds of HF servers around, but even easier, there are now dozens of VHF and UHF servers around Michigan.

|

| Connections |

You connect your computer to the radio using a TNC. Most modern programs don't require a lot of smarts in the TNC, so there is little advantage to an expensive TNC over a cheap one.

The most common program is Winlink Express. But this requires leaving your computer connected to the TNC, which may or may not be convenient, or switching to a dedicated computer. Again, not as convenient as it might be.

Of course, these days, everything we do seems to involve a Raspberry Pi. This is a really cheap computer we can dedicate to a task. Better yet, there is a cheap TNC available for the Raspberry Pi called a TNC-Pi. And to top it off, there is a Winlink client called pat that will present itself as a web page. So if you put a Pi with a TNC-Pi on your LAN, you can send and receive Winlink messages over VHF or UHF from any web browser on your LAN.

I will detail below how to make this work for you. You will need a Pi, and a TNC-Pi. I am using a Raspberry Pi model 3B+ and a TNC-Pi 2. Older TNC-Pi models will be the same, and older Pi models should be virtually identical. You will also need a keyboard, mouse and display, but once the system is configured these are no longer needed. I am assuming that you will connect the Pi into your LAN ver a normal Ethernet, so you will also need an Ethernet cable. For newer Pi models you could also use WiFi, but I won't go into setting up WiFi.

I tend to find an unusual keyboard annoying, so once the first few setup steps are done, I use SSH from my regular computer. Linux and Mac have built in SSH clients. I found that MobaXterm is a very nice SSH client for Windows. You could also use PuTTY, but it is somewhat limited. I understand that the PowerShell in Windows 10 has an SSH client, but have not tried that.

So, start by getting your TNC-Pi built and tested. Go through the steps outlined in the TNC-Pi manual to set up and test ax25-tools on your Pi.

One change I made to W2FS's instructions; I named my port wl2k instead of 1. I find that I tend to overlook 1 on some commands, and that field is a text field, so if you have named your TNC-Pi Suzie, then you could call the port Suzie.

|

| axports |

| kissattach command |

You should now be able to do the axcall command outlined in the TNC-Pi documents replacing 1 with your preferred name.

pat

Now that you have your TNC-Pi installed and tested, time to get on with making the Winlink client work. Download and install the .deb package from

https://github.com/la5nta/pat/releases/download/v0.6.1/pat_0.6.1_linux_armhf.deb

following the instructions at

https://github.com/la5nta/pat/wiki/Install-FAQ

You are going to want your web interface to be available all the time. To make that happen, you are going to want to have a dedicated user on the Raspberry Pi. I chose the creative user name winlink. You will not want to log on to this user once pat is set up.

Log on to the user and type

pat config

You will enter the editor with the configuration file. Once you have run pat for the first time, you may instead prefer to edit ~/.wl2k/config.json with your favorite editor.

You need to tell pat what relays you will be connecting to.

|

| Part of config.json |

The "http_addr" is significant. In most cases you will probably be using an IP address assigned by your router. You can use ifconfig to determine this number.

|

| ifconfig |

"http_addr": "192.68.0.38:8080",

Depending on your router, you maybe able to cause the router to assign a specific address to the Pi's MAC address, shown as "ether" above. This number is unique to every device.

Depending on your LAN, you might be able to assign a friendlier name to that address. In my case, I called it "pat01". This name or address must match what address you give your browser. In this case, you might expect I could connect with 192.68.0.38 but in fact, pat won't answer to that address, even though it is the Pi's address.

The aliases are optional, but they will appear in the (select alias) menu when you connect. For an RMS you can reach directly, the format is:

Once you have saved the config file, type

pat http

and return to your "normal" computer, leaving pat running on the Pi.

Using pat

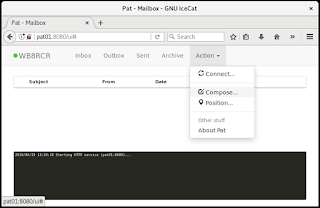

Open your web browser, and type the address in the "http_addr" line into the web browser's address bar. You should see something like:

|

| pat - nothing in inbox |

If you do not have a Winlink account, leave the password blank, and then simply connect and not send a message. Then connect again and you will receive a message with your Winlink password. Put that password in your configuration.

Now, to prove we have a working pat, let's send ourselves a Winmail message using the Internet. Click on Action, then Compose...

You will see the compose a message dialog:

Put your call into the To: box and formulate a dummy message. Click on Post to post the message to the Outbox.

Next, select Connect... from the Action menu. The sending dialog will appear:

Choose telnet from the (select alias) menu then click Connect. You will see some activity in the black area at the bottom of the window. It should end up something like:

Any messages in your Outbox will be sent to the server.

Now connect again, and your message should be seen in the Inbox.

Setting pat to start automatically

Now that we have it working, we would like it to start on boot so that we never have to actually log in to the Pi.

If you haven't already, stop pat (with Cntl-C).

Then add the following two lines to the bottom of ~/.bashrc:

sudo kissattach /dev/serial0 wl2k 10.1.1.1

/usr/bin/pat http

where wl2k is your port name. If you have an assigned 44.x IP address you may choose that instead of 10.1.1.1, but since it isn't used in the case, it won't matter. It could be handy, tho, if you log on to the Pi and want to work with a node that supports the Internet Protocol.

At this point you may wish to log off and log back on again to be sure pat starts automatically. You will need to stop pat in order to log off.

Assuming you installed the default Raspbian distribution, you can do the next steps logged on as the pi user, which is logged on the the graphical console by default.

Edit /etc/systemd/logind.conf. Uncomment the first two lines after [Login] and change both 6 to 5:

[Login]

NAutoVTs=5

ReserveVT=5

#KillUserProcesses=no

...

Now, cd to /lib/systemd/system/

Copy getty@.service to pat-winlink.service

sudo cp getty@.service pat-winlink.service

Edit pat-winlink.service as follows:

Change

Description=Getty on %I

to

Description=Winlink client on tty6

Change

ExecStart=-/sbin/agetty --noclear %I $TERM

to

ExecStart=-/sbin/agetty --noclear tty6 38400 -a winlink

where winlink is the user code you chose to run pat.

At the bottom of the file change

[Install]

WantedBy=getty.target

DefaultInstance=tty1

to

[Install]

Alias=getty.target.wants/pat-winlink.service

Now you need to let the system know you have messed with these files:

systemctl daemon-reload

If you have logged off your winlink user, you should now be able to start pat by typing:

sudo systemctl start pat-winlink

and cause it to start automatically with:

sudo systemctl enable pat-winlink

You can (and should) check the status of pat with:

sudo systemctl status pat-winlink

the result should be something like:

|

| pat service status |

pat should now start whenever the Pi is rebooted.

Finding an RMS

If you go to https://winlink.org/RMSChannels you will get a map of RMSs. With the TNC-Pi you will only be able to connect to packet RMSs, so click on the Packet button and zoom the map to the appropriate area:If you then click on one of the markers, you can see detail about that RMS:

Turn your radio to the desired frequency, put the callsign into the target: box on the connect dialog, and you should be able to send and receive messages over the radio.

If you use an ordinary email address instead of just a callsign, the message will be delivered over email. You can be reached by email at (your call)@winlink.org if the sender has received a Winlink message from you in the past few months.

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

Pi Toppings

Boy, labels can really help.

As soon as I had a few Raspberry Pis, I began to realize that knowing what the MAC address was for a Pi was handy, so I put a label on each Ethernet connector with the MAC address.

In working on the Midland Hamgate with multiple TNCs, I was having some initial issues that seemed to be related to the particular Raspberry Pi. At that point it became obvious that I needed quick access not only to the MAC address, but to the name my dnsmasq server would assign to that Pi. So, more labels:

At first I had two TNCs, one for my home JNOS and one for my portable JNOS. But the Midland Hamgate will require multiples, which means assigning an I2C address to each TNC. Since I can't see what I2C address is programmed, and it is pretty clumsy to even read it once JNOS is running, labels for the I2C addresses seemed necessary:

OK, that was pretty good, but once I started doing RF testing it became evident that it is useful to know what frequency the TNC is assigned to. Even more important, once it is in service it will be very handy for debugging, so:

So now my TNCs are all covered with stickers, but they seem to like it. As best I can tell, they are all working:

As soon as I had a few Raspberry Pis, I began to realize that knowing what the MAC address was for a Pi was handy, so I put a label on each Ethernet connector with the MAC address.

In working on the Midland Hamgate with multiple TNCs, I was having some initial issues that seemed to be related to the particular Raspberry Pi. At that point it became obvious that I needed quick access not only to the MAC address, but to the name my dnsmasq server would assign to that Pi. So, more labels:

|

| MAC and nodename labels |

|

| I2C address labels |

|

| Channel Labels |

So now my TNCs are all covered with stickers, but they seem to like it. As best I can tell, they are all working:

| ||

| Heard List |

Labels:

Amateur Radio,

I2C,

JNOS,

Packet,

Raspberry Pi,

TNC-Pi

Location:

Midland, MI, USA

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

More Pi-JNOS fun

So, you have your TNC-Pi built, JNOS up and running on your Pi, but you know there are things that you could be doing, but don't know how. Well, let's do a (very) short tutorial on bash and the crontab.

bash is the Linux equivalent of the DOS batch files, but it is way more powerful. crontab is the scheduler which lets you have your Pi do things at a predetermined time.

Unlike DOS, file extensions don't mean a lot to Linux. But they are often used, and some programs pay attention. For example, many graphics programs expect a file with the extension .jpg to be a JPEG image.

The command ls for listing files has settings that can cause certain extensions to be listed in specific colors. By default in Pidora, images and videos are purple, sound files light blue, and archives of various types red. In addition, files with executable permission are shown in green, and directories in blue:

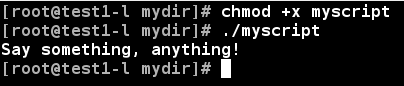

When you write a "batch file" (in Linux called a bash script), it must have an executable permission. You give it that permission with the chmod command:

chmod +x myscript

By default, unlike DOS, the current directory is not on the path, so to execute a script you must specify the path. For example:

./myscript

(like DOS, the current directory is . and recall that in Linux, you separate directory levels by / rather than \.

It is traditional, and sometimes helpful, for bash scripts to begin with the line:

#!/bin/sh

And like DOS, we can type commands to be executed, and there is an echo command which displays to the terminal. So if we had a bash script like:

#!/bin/sh

echo "Say something, anything!"

It would echo to the terminal:

Notice that some of the commands seem a little odd. We have already seen that the ls command is kind of like the DOS DIR command. There actually is a Linux dir command, but it is rarely used because it isn't nearly as flexible as ls, which has dozens of options.

You can learn about the options of ls, or any command, by typing man followed by the command. For example, man ls gives the following screen:

You can page back and forth, in this particular case there are about 11 screens of information. You can even search for specific things within the man page.

bash scripts may also have variables. You can assign a value to the variable with the equal sign. Since most Linux commands are lower case, it is customary to make variable names upper case so they stand out.

You can use the variable by placing a $ before its name. Because there could potentially be some confusion on where the variable name ends, it can be a little safer to enclose the name in curly braces, but this isn't usually necessary.

So if we add a little something to the script:

#!/bin/sh

MYSTRING="dadadididit didididadah"

echo "Say something, anything!"

echo "Here is a string -- ${MYSTRING}"

The result would be:

So far not all that exciting, but there are a few neat features. bash can loop through the words in a string, which can often be very handy. For example:

You can also assign the result of a command to a variable by surrounding the command with backward quotes (on most keyboards at the upper left under the tilde).

So for example:

The date command is amazingly flexible. See the man page for details. JNOS names its log files as a two digit day of the month, a three character month, and a two character year. So the log for February 4th, 2014 would be 04Feb14.

Suppose I want to move all of last month's logs files into a single zip file. I want to do this after the month is over, so I want last month's date. To further mess things up, I would like the month in the name of the zip file to be numeric, so when I look at a directory listing they are shown in some sensible order.

So, let's consider the following script:

#!/bin/sh

# Get the various date pieces:

# Month as a 3 character string

MONTHA=`date -d "15 days ago" +"%b"`

# Month as a 2 digit number

MONTHN=`date -d "15 days ago" +"%m"`

# Year as a two digit number

YEAR=`date -d "15 days ago" +"%y"`

cd /jnos/logs

zip -om9 Log${YEAR}${MONTHN} *${MONTHA}${YEAR}

The -d switch tells the date command to use the specified date rather than the current date. There are a number of ways to specify a date, but since I might not get to run this right at the first of the month, "15 days ago" is very likely a date in last month.

The date command also gives me plenty of options for formatting the date. The + sign tells the command that a format is to follow. The formats used here return the date as a three character month name, a two character month number, and the last two digits of the year.

If I were to run this today, February 4, 2014, this would move all files in /jnos/logs with names *Jan14 into a zip file named Log1401.zip.

If you are not familiar with the zip switches, -o says to set the date on the zip file to the same as the newest file in the zip, -m says to move files to the zip rather than copy, and -9 says to use maximum compression. Following common Linux practice, one-character switches can be stuck together behind a single minus sign.

Linux has another neat feature called the crontab. This is a table of things to do at specific times. Each user has his own table. You can list the crontab with:

crontab -l

and edit the crontab with

crontab -e

The lines in the crontab have a kind of peculiar format. There are five numbers, separated by spaces, a tab, and then a command. The five numbers are minutes, hours, day of the month, month and day of the week. An asterisk may be used to mean every possibility. Multiple occurrences can be separated by commas.

If we called our script compLogs.sh and stored it in a directory called bin off our home directory, the cron line:

36 8 3 * * bin/compLogs.sh

would cause our script to be run at 8:36 A.M. on the third of every month.

I have a script that sends a finger command to the hamgate four times a day to check the health of the hamgate. The crontab entry:

0 0,6,12,18 * * * /root/finger-hamgate

causes the script to run at midnight, 6 A.M., noon and 6 P.M. every day. Notice that I have multiple hours separated by commas.

This can get pretty gangly. The Midland hamgate grabs radar images from NWS every five minutes. Although this could have been done on one line, there are three entries just to make it a bit more readable:

2,7,12,17,22 * * * * bin/WxImages.sh

27,32,37,42,47 * * * * bin/WxImages.sh

52,57 * * * * bin/WxImages.sh

Generally it is good practice to start cron jobs at odd times if possible. Since there can be multiple cron tabs, if you make a habit of starting jobs at the top of the hour it can cause things to get real busy at certain times, and you might even have a hard time recognizing why. These things tend to be "out of sight, out of mind" in pretty short order. By starting jobs at odd times, you reduce the odds that a large number of jobs will start at the same time.

There are lots an lots of bash features that I haven't mentioned. There are plenty of references, but the real flexibility of bash comes from your imagination, and that is tough to get from a book. Best plan is to play around, write a bunch of scripts, and when you find something you don't know how to do, look through the man pages, online references, and ask around. Chances are you can't figure it out because it's so obvious!

As you do this, one man feature that is really handy is a keyword search. The -k for keyword switch allows you to search all the man pages for a particular keyword, so if you want to do something and don't know the command, this might help. For example, if I wanted to see what the man pages know about ax25:

So go have some fun!

bash is the Linux equivalent of the DOS batch files, but it is way more powerful. crontab is the scheduler which lets you have your Pi do things at a predetermined time.

Unlike DOS, file extensions don't mean a lot to Linux. But they are often used, and some programs pay attention. For example, many graphics programs expect a file with the extension .jpg to be a JPEG image.

The command ls for listing files has settings that can cause certain extensions to be listed in specific colors. By default in Pidora, images and videos are purple, sound files light blue, and archives of various types red. In addition, files with executable permission are shown in green, and directories in blue:

When you write a "batch file" (in Linux called a bash script), it must have an executable permission. You give it that permission with the chmod command:

chmod +x myscript

By default, unlike DOS, the current directory is not on the path, so to execute a script you must specify the path. For example:

./myscript

(like DOS, the current directory is . and recall that in Linux, you separate directory levels by / rather than \.

It is traditional, and sometimes helpful, for bash scripts to begin with the line:

#!/bin/sh

And like DOS, we can type commands to be executed, and there is an echo command which displays to the terminal. So if we had a bash script like:

#!/bin/sh

echo "Say something, anything!"

It would echo to the terminal:

Notice that some of the commands seem a little odd. We have already seen that the ls command is kind of like the DOS DIR command. There actually is a Linux dir command, but it is rarely used because it isn't nearly as flexible as ls, which has dozens of options.

You can learn about the options of ls, or any command, by typing man followed by the command. For example, man ls gives the following screen:

You can page back and forth, in this particular case there are about 11 screens of information. You can even search for specific things within the man page.

bash scripts may also have variables. You can assign a value to the variable with the equal sign. Since most Linux commands are lower case, it is customary to make variable names upper case so they stand out.

You can use the variable by placing a $ before its name. Because there could potentially be some confusion on where the variable name ends, it can be a little safer to enclose the name in curly braces, but this isn't usually necessary.

So if we add a little something to the script:

#!/bin/sh

MYSTRING="dadadididit didididadah"

echo "Say something, anything!"

echo "Here is a string -- ${MYSTRING}"

The result would be:

So far not all that exciting, but there are a few neat features. bash can loop through the words in a string, which can often be very handy. For example:

You can also assign the result of a command to a variable by surrounding the command with backward quotes (on most keyboards at the upper left under the tilde).

So for example:

The date command is amazingly flexible. See the man page for details. JNOS names its log files as a two digit day of the month, a three character month, and a two character year. So the log for February 4th, 2014 would be 04Feb14.

Suppose I want to move all of last month's logs files into a single zip file. I want to do this after the month is over, so I want last month's date. To further mess things up, I would like the month in the name of the zip file to be numeric, so when I look at a directory listing they are shown in some sensible order.

So, let's consider the following script:

#!/bin/sh

# Get the various date pieces:

# Month as a 3 character string

MONTHA=`date -d "15 days ago" +"%b"`

# Month as a 2 digit number

MONTHN=`date -d "15 days ago" +"%m"`

# Year as a two digit number

YEAR=`date -d "15 days ago" +"%y"`

cd /jnos/logs

zip -om9 Log${YEAR}${MONTHN} *${MONTHA}${YEAR}

The -d switch tells the date command to use the specified date rather than the current date. There are a number of ways to specify a date, but since I might not get to run this right at the first of the month, "15 days ago" is very likely a date in last month.

The date command also gives me plenty of options for formatting the date. The + sign tells the command that a format is to follow. The formats used here return the date as a three character month name, a two character month number, and the last two digits of the year.

If I were to run this today, February 4, 2014, this would move all files in /jnos/logs with names *Jan14 into a zip file named Log1401.zip.

If you are not familiar with the zip switches, -o says to set the date on the zip file to the same as the newest file in the zip, -m says to move files to the zip rather than copy, and -9 says to use maximum compression. Following common Linux practice, one-character switches can be stuck together behind a single minus sign.

Linux has another neat feature called the crontab. This is a table of things to do at specific times. Each user has his own table. You can list the crontab with:

crontab -l

and edit the crontab with

crontab -e

The lines in the crontab have a kind of peculiar format. There are five numbers, separated by spaces, a tab, and then a command. The five numbers are minutes, hours, day of the month, month and day of the week. An asterisk may be used to mean every possibility. Multiple occurrences can be separated by commas.

If we called our script compLogs.sh and stored it in a directory called bin off our home directory, the cron line:

36 8 3 * * bin/compLogs.sh

would cause our script to be run at 8:36 A.M. on the third of every month.

I have a script that sends a finger command to the hamgate four times a day to check the health of the hamgate. The crontab entry:

0 0,6,12,18 * * * /root/finger-hamgate

causes the script to run at midnight, 6 A.M., noon and 6 P.M. every day. Notice that I have multiple hours separated by commas.

This can get pretty gangly. The Midland hamgate grabs radar images from NWS every five minutes. Although this could have been done on one line, there are three entries just to make it a bit more readable:

2,7,12,17,22 * * * * bin/WxImages.sh

27,32,37,42,47 * * * * bin/WxImages.sh

52,57 * * * * bin/WxImages.sh

Generally it is good practice to start cron jobs at odd times if possible. Since there can be multiple cron tabs, if you make a habit of starting jobs at the top of the hour it can cause things to get real busy at certain times, and you might even have a hard time recognizing why. These things tend to be "out of sight, out of mind" in pretty short order. By starting jobs at odd times, you reduce the odds that a large number of jobs will start at the same time.

There are lots an lots of bash features that I haven't mentioned. There are plenty of references, but the real flexibility of bash comes from your imagination, and that is tough to get from a book. Best plan is to play around, write a bunch of scripts, and when you find something you don't know how to do, look through the man pages, online references, and ask around. Chances are you can't figure it out because it's so obvious!

As you do this, one man feature that is really handy is a keyword search. The -k for keyword switch allows you to search all the man pages for a particular keyword, so if you want to do something and don't know the command, this might help. For example, if I wanted to see what the man pages know about ax25:

So go have some fun!

Labels:

Amateur Radio,

bash,

cron,

JNOS,

Linux,

Packet,

Raspberry Pi

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)